Olympic Lifting vs. Powerlifting: Similarities & Benefits

This is a guide to Olympic lifting vs. powerlifting. Find out the key moves from these weightlifting disciplines and understand the techniques behind each.

If you’re getting serious about lifting, you may eventually find yourself in a position where you’re catapulted into the realm of competitive lifting.

Weightlifting has hogged the spotlight in sports for the last several years. There’s evidence to show that lifting heavy stuff up and putting it down is one of the best ways to preserve your long term health.

Resistance training, whether at high or low frequency, has a major impact on increasing your body’s stores of lean muscle. You can learn more by reading Increasing Lean Mass and Strength.

But many people, even those who lift themselves, aren’t well-versed in the different styles of lifting and how you need to adapt your training for each. Whether you are lifting to get a lean vs. bulky body, there are a few key details about weightlifting that you should know.

Two of the most common competition styles are powerlifting and Olympic lifting. Let’s take a look at the origins of each style, which major lifts are involved in these competitions and what type of training you’ll need to do for Olympic lifting vs. powerlifting.

What is Olympic Lifting?

In Olympic weightlifting, athletes lift a loaded barbell off the ground and overhead.

Olympic weightlifting has two key lifts.

Snatch

In the snatch, athletes lift a barbell from the ground to overhead in one swift move. This is a pure power move that requires many small technical adjustments to perfect.

Sweeping the barbell up and overhead requires a hyperfocused mind-muscle connection.

Clean and Jerk

The clean and jerk is comprised of two moves: the clean and the jerk. In the “clean” part of this move, the athlete lifts a barbell from the ground to a racked position across the tops of their front delts.

After that comes the “jerk.” Here, a lifter hoists the barbell all the way up into the air in a swift overhead press. The arms come to a straight position and the barbell sits as high as possible in the air.

Olympic Lifting History

The concept of weightlifting dates back as far as Ancient Greece where men lifted boulders, rocks or other heavy objects as a test of their masculinity. Most modern lifting styles were derived from weightlifting, which spawned from even older strongman competitions.

Weightlifting popped up at the Olympics for the first time in 1896. In this contest, held at the Pantheanic Stadium in Greece, men had a chance to perform two lifts: a one-handed lift and a two-hand lift.

Eventually, in 1905, a Weightlifting Federation was formed and the sport was recognized by the International Olympic Committee in 1914. In 1920, weightlifting formally became an Olympic sport.

Olympic Weightlifting Physique

So what do Olympic lifters look like anyway? This sport has a range of different body types that tend to do well. Everything from a lean and cut body to borderline obese lifters with high body fat percentages have excelled in Olympic weightlifting.

Although the aesthetics of Olympic lifting can vary greatly, the emphasis that it puts on certain muscle groups based on the types of lifts you do tend to result in growth in certain areas.

Because the key lifts Olympic weightlifters do are overhead of upper body focused, there’s less emphasis on the thighs and glutes, for example, when compared to the squats and deadlifts of powerlifting.

In Olympic lifting, you can expect to see highly developed core muscles. Whether shredded or barrel-chested, the stability Olympic lifters need for a clean and jerk or snatch all comes from the abs.

What is Powerlifting?

Athletes who powerlift get three attempts to go for a maximum weight lift in three categories. The sports originated from another type of competitive lifting called “odd lifts.” Here, there was a greater variety of lift types that competitors could hone in on. Finally, they narrowed powerlifting down to three key lifts.

Powerlifting focuses on:

Squats

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’re likely familiar with squats. From hack squat variations to unweighted squats, pretty much anyone can squat in some way. Whether you are working through pistol squat progressions, traditional squat progressions, reverse hack squats or other hack squat alternatives, there’s a squat for everyone!

Powerlifting squats, however, look a little different from the ones you’re used to doing on the rack at your local Planet Fitness.

This is the first event in a powerlifting skills competition. Usually, two spotters (one on each side) that understand how to spot a squat will assist you. The walkout after you step under the barbell to unrack it onto your shoulders usually takes about 2-4 steps.

If you’re squatting on your own, you can take as many steps as you please. In powerlifting competitions, you can use any grip that you prefer on your barbell.

That being said, an analysis of Classic Powerlifting Performance from the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research evidence shows that a low bar squat and a wide grip bench press were the most optimal for competitive powerlifters to move heavier loads and prevent injuries.

Competitors are allowed to shuffle their feet around until they are given the “squat” command.

Here, you can’t reposition your feet. You’ll have to squat down to your best squat depth and come up on your own time, locking out your knees at the top of your squat.

Bench Press

Bench pressing is one of the best ways to increase your upper body strength. This feat of Herculean strength involves pressing a heavily weighted barbell over your chest and fully extending your arms to hold it in the air.

The International Powerlifting Federation has strict guidelines on the range of motion and posture that lifters need to follow when bench pressing in a competition. The bench press is one of the best indicators of overall upper body strength.

If you’re looking for tips on how to up your bench press weight, chek out How to Bench More.

Deadlifts

Deadlifts are one of the most effective moves when it comes to growing your hamstrings and glutes in powerlifting competitions.

Here, an athlete lifts a loaded barbell off the ground to hip level.

Powerlifting Competitions and History

Powerlifting is primarily regulated by the International Powerlifting Federation. It is practiced as a World Games sport. Organizers also offer Paralympic powerlifting, however, this is limited to bench press only.

The concept of powerlifting dates back as far as Ancient Greece where men lifted boulders, rocks or other heavy objects as a test of their masculinity to work out like the Greek Gods. Most modern powerlifting was derived from weightlifting, which spawned from even older strongman competitions.

After the International Powerlifting Federation was founded in 1972, the sport increased in popularity and started to become more standardized.

Powerlifter Body

Powerlifters are known for their massive bodies. Hafthor Bjornsson, for example, the athlete-turned-actor who portrayed The Mountain on Game of Thrones is a competitive powerlifter and strongman.

At an absolutely massive 6’9 inches tall and with a weight of over 400 pounds, this guy is an absolute unit. Bodies like this are commonly what we associate with powerlifting. Although powerlifters have a lot of muscle, typically, their physiques come with a good amount of fat too.

Basically, these guys are bulky and their massive size helps them achieve one-rep maxes (1RMs) that showcase maximum strength.

Which is Better Powerlifting or Olympic Lifting?

Powerlifting prizes an explosive movement quality, while Olympic lifts are tailored to develop overall strength.

Depending on what your goals are, you may prefer one or the other. If you’re training at a regular gym, it’s probably easiest to train powerlifting moves like squats, bench presses and deadlifts.

Both of these exercises, at least at a competitive level, rely on a test of proven strength using three sample lifts of a one-rep max. So each lift, the deadlift, the bench press, the squat, or in the case of Olympic lifts, the clean and jerk and the snatch, would be repeated three times per competition.

You can read more about the one-rep max as a metric in: Reliability of the One-Repetition Maximum Test.

Although many find the snatch and clean and jerk fun to do, because of their explosiveness, they’re a bit more volatile. It’s helpful to have trained spotters on hand for these complex lifts. Otherwise, you risk putting yourself or others in danger.

If you train at, say, a CrossFit gym that works with a lot of non-traditional movements, you may have an easier time working on snatch and clean and jerk lifts.

These sports are ruled by different muscle fiber types. Where powerlifting comes from more of your type IIA muscle fibers, Olympic lifts require more type IIA fiber activation. IIB muscle fibers are associated with shorts bursts of maximal power and explosiveness, like you’d need to lift a barbell in the snatch.

IIA fibers, on the other hand, are more linked to sustained power, which is more evident in powerlifting moves. Although both sports require you to lift your 1RM for three lifts, powerlifting requires less of a burst of energy.

To learn more, you can read Muscle Fiber Type Transitions with Exercise Training.

The Takeaway

Which is a preferable training style between Olympic lifting vs. powerlifting?

Ultimately, it’s the one that you’ll do consistently and that you enjoy more. With any training style, there is no “right” or “wrong” type of exercise. The main point is that you like the lifts you’re doing and that they’re repeatable and accessible to your current skill level.

Olympic lifting focuses on the snatch and the clean and jerk. These moves are fun and explosive but may be challenging or awkward to replicate in a traditional gym environment.

On the other hand, powerlifting involves heavy squats, deadlifts and bench presses. There are fundamental strength builders and can be done pretty much anywhere that you have heavy weights for training.

If you love to lift, you may want to try out a combination of both Olympic lifts and powerlifting moves as part of your regular training routine.

This is a great option, just make sure you take the time to recover well.

References

Ferland, P. M., & Comtois, A. S. (2019). Classic Powerlifting Performance: A Systematic Review. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 33 Suppl 1, S194–S201. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003099

Herbison, G. J., Jaweed, M. M., & Ditunno, J. F. (1982). Muscle fiber types. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 63(5), 227–230.

Plotkin, D. L., Roberts, M. D., Haun, C. T., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2021). Muscle Fiber Type Transitions with Exercise Training: Shifting Perspectives. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 9(9), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports9090127

Seo, D. I., Kim, E., Fahs, C. A., Rossow, L., Young, K., Ferguson, S. L., Thiebaud, R., Sherk, V. D., Loenneke, J. P., Kim, D., Lee, M. K., Choi, K. H., Bemben, D. A., Bemben, M. G., & So, W. Y. (2012). Reliability of the one-repetition maximum test based on muscle group and gender. Journal of sports science & medicine, 11(2), 221–225.

Thomas, M. H., & Burns, S. P. (2016). Increasing Lean Mass and Strength: A Comparison of High Frequency Strength Training to Lower Frequency Strength Training. International journal of exercise science, 9(2), 159–167.

Related articles

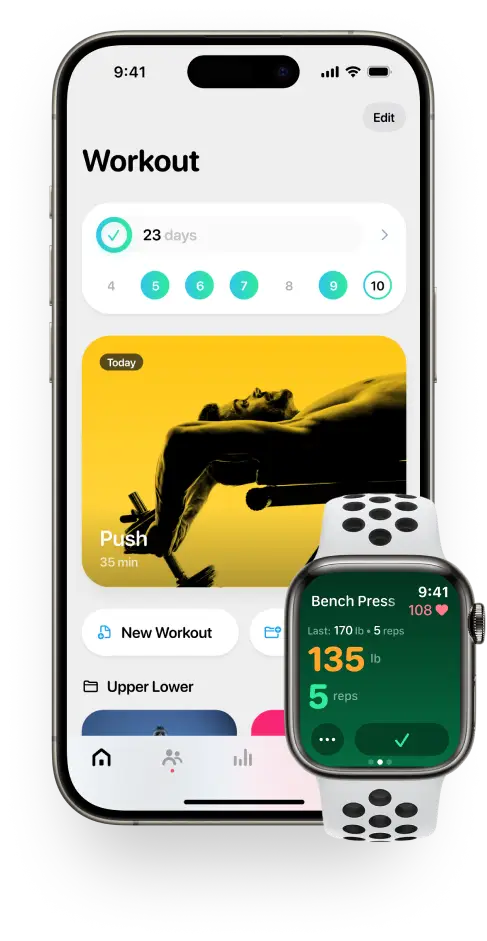

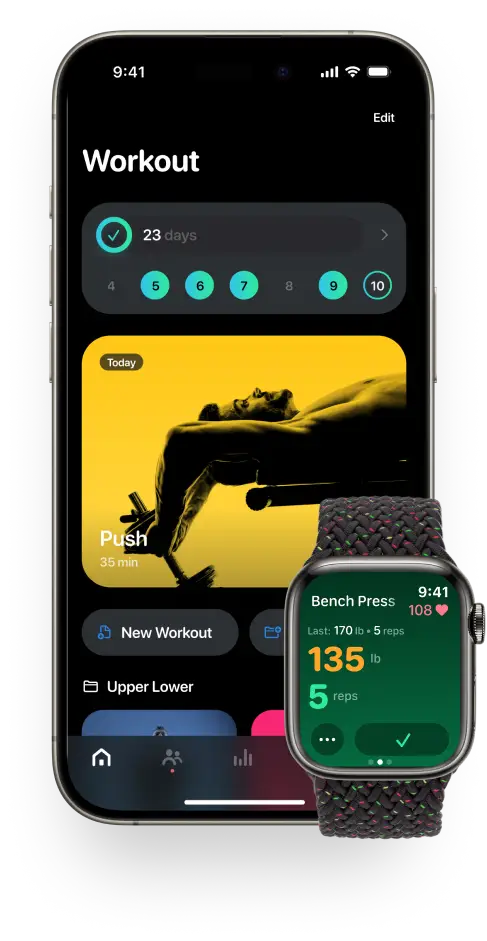

Get fit with Flex

Build muscle & lose weight fast for free.

Available on iPhone + Apple Watch