Bad Chest Genetics: What Are the Signs & Can You Fix Them?

What are bad chest genetics? Learn about the signs of bad chest genetics. Understand how you can work around your genes and grow your chest.

If you find that your chest progress has stalled while you're working out, you might question whether your training routine is to blame or if there's a more underlying issue, like bad chest genetics.

This article will examine how your genes influence your ability to grow your chest muscles and whether there are exercises you can do to fix even the worst chest genetics.

What Are Bad Chest Genetics?

Although ultimately, what’s defined as “bad” is different for everyone, here are a few things that some people consider to be bad chest genetics.

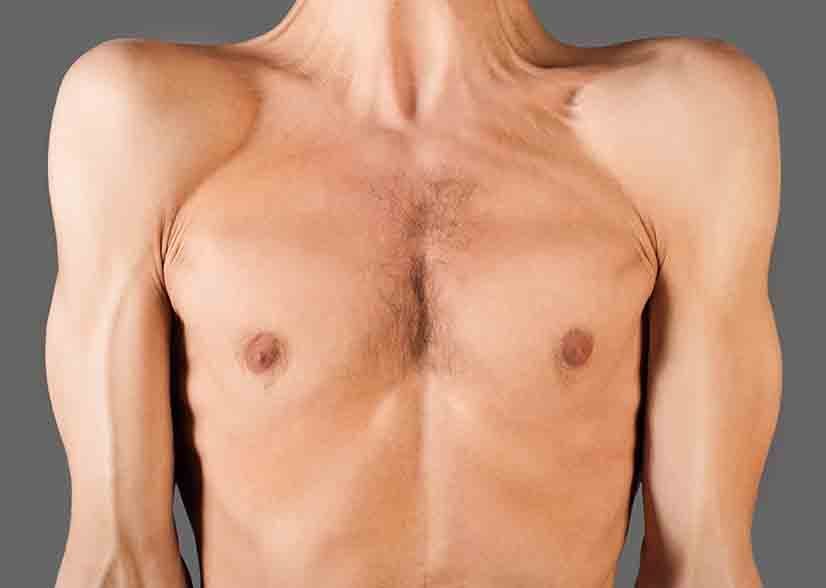

1. Chest Gap

If you have a gap between your pectoral muscles, it may be a genetic occurrence.

Typically, a chest gap is caused by how your pectoral muscles separate. Anatomy-wise, our sternum is the bone in between your chest muscles that isn’t covered by any muscles. Your pectorals, aka your chest muscles, sit on either side of the sternum.

Larger or more developed pecs can cover your sternum, so you have no chest gap visible.

However, if your genes aren’t conducive to a lot of chest muscle growth or your pecs simply sit wider apart due to genes, you may be able to see more of a gap in between.

Are chest gaps dangerous?

Not usually! Unless you have certain medical conditions that give the look of a gap or groove (more on these later) traditionally, a gap won’t pose a threat to your health. It’s mostly an aesthetic preference.

2. Narrow Clavicles

Narrow clavicles, aka collarbones that don’t create a lot of width across your shoulders, can be considered bad chest genetics.

If you have narrow clavicles, your chest may seem to be drooping downward. This type of collarbone can also give you the look of sloped shoulders.

3. Misshapen Chest

There are a few medical conditions that can leave you with what looks like either a dent or a bump in the middle of your chest.

- Pectus excavatum: This condition causes you to have a dip or dent in the middle of your chest.

- Pectus carinatum: This condition looks opposite to pectus excavatum. Here, your chest will have a large, bony bump that protrudes from the center.

So if you asked yourself “what are signs of bad chest genetics?” these issues are a few telltale signs to look out for.

Although most won’t be medically dangerous, a misshaped chest, narrow clavicles or a gap between your pecs can prove to be “bad chest genetics” if you’re focused on aesthetics and muscle building.

When Should I Be Worried About a Bad Chest?

A bad chest can feel worrisome at any time if you’re focused on looks.

Generally, though, you don’t need to be too concerned about bad chest genetics unless it impacts necessary body processes.

If a bad chest causes you to experience:

- Shallow breathing

- Digestion issues

- Severe mental or emotional distress

- Chronic pain or prolonged soreness

It’s a good idea to seek help, as you may be dealing with a more serious health concern.

How to Fix Bad Chest Genetics

Workouts can help you achieve a strong-looking chest, even with mediocre or poor chest genetics!

Targeted exercises are a simple way to work around your chest genetics. Take a look at 3 simple workouts you can do to improve the look and strength of your chest even with poor genes.

Sure, here are three simple chest workouts, each containing three exercises:

Sample Workout 1

- Push-Ups

- Dumbbell Bench Press

- Chest Flyes

Workout 2

- Incline Push-Ups

- Dumbbell Pullover

- Cable Chest Press

Workout 3

- Decline Push-Ups

- Chest Dips

- Dumbbell Floor Press

Try to perform at least 3 chest moves per workout if you’re concerned about growth. This way, you make your chest a priority and can really help the muscles grow.

If you’re working other muscles along with your chest, for example, a push day workout, start with a chest exercise.

This way your muscles are fresh when you’re training your chest. You’ll most likely be able to lift a bit heavier and feel less fatigued if you train your chest first.

Good Chest Genetics vs Bad

How do you know if you have good vs. bad chest genetics? Some signs of good chest genetics include:

1. Even size

Most people consider a good chest to mean one that has even volume through the upper and lower parts of the pectoral muscles.

This creates a balanced and harmonious look to your upper body.

You’re also likely to suffer from less strength discrepancies between the upper and lower chest, since balanced muscle size is a good indicator that you’re training the muscles evenly.

2. Wide clavicles

For men especially, the look of wide clavicles or broad shoulders can be more aesthetic and will tie together a strong chest. The shoulder muscles and chest muscles often work together, so broader shoulders can be considered a component of good chest genetics.

3. Muscular strength

Finally, chest muscles that perform the way you want them to are the most genetically optimal. If you find ease in “push” day exercises that work the chest, like push-ups or bench presses, you may have better chest genetics than most.

Bad Upper Chest Genetics

Can you have bad upper chest genetics but good lower chest genetics?

The chest gap can be a sign of bad genetics impacting your upper chest. Typically, your genetic capacity to grow muscle would impact your whole chest (and all the other muscles in your body).

That being said, many weightlifters find it hardest to build mass in their lower chest region compared to the upper. This may be due to a mix of genetic factors and improper training.

If you want to single out the upper chest for growth, focus on:

- Using an incline for your bench press

- Decline push-ups, keeping your arms in line with your body (no elbow flare)

To get a fuller lower chest on the other hand, try

- Decline bench presses

- Incline push-ups

What Are the Chest Muscles?

Your chest muscles are also called the pectoral muscles, aka “pecs.” The main muscles of your chest are large, fan-shaped muscles called the pectoralis major.

The pecs attach to your upper arm bones (humerus bones), span across the top of your chest at your collarbones (clavicles) and attach to your sternum, the bone in the middle of your chest.

These muscles help you move your arms across your body and up and down.

Other chest muscles include:

- Pectoralis minor

- Serratus anterior

- Subclavius

Is Your Chest Size Genetic?

Most of the way your chest is shaped and size comes down to your genes. This has to do with your bone structure and your genetic ability to build muscle.

What genes determine your muscle-building capabilities and therefore can factor into your chest size?

The ACTN3 gene is one of the most commonly associated genes with building muscle. Professional athletes often have higher-than-average occurrences of this gene.

The ACTN3 gene encodes a substance called alpha-actinin-3. This is a protein expressed only in type-II muscle fibers. Type II fibers, aka “fast twitch” muscle fibers are associated with power and speed. These types of fibers may help you put on skeletal muscle more quickly and easily.

If you have good chest genetics, it’s possible that this gene may be helping you out.

Why is My Chest so Wide?

Your chest could be wide for a few reasons. Typically, a wider or narrower chest is a result of the size and width of your clavicles and ribcage.

Most of this bone structure is genetically determined.

Your chest width could also be due to excess body fat. If you’re overweight, you may simply store more fat in the chest area, making it wider compared to the rest of your body.

For men, a common condition resulting in excess chest size is gynecomastia.

You’ve probably heard this condition referred to as “man boobs.” The name’s not entirely wrong: gynecomastia causes more breast tissue than usual to develop in men.

Although men also naturally have some breast tissue, a hormonal imbalance in the amount of estrogen or testosterone can cause even more to develop.

Although gynecomastia is usually benign, it may cause embarrassment or unwanted width around your chest.

Big Picture

Whether your chest genetics are ideal or not largely depends on your training and personal aesthetic goals. Though many people, especially men prefer a wider chest with broad shoulders and and gap-free pecs, as long as your chest can perform the exercises you need it to, there’s no reason to get discouraged about your genes.

Conditions that affect your chest like pectus excavatum and gynecomastia typically cause more aesthetic concerns than physical harm.

If you struggle with either of these conditions mentally or physically, it may be a good idea to speak with a doctor or therapist. A professional can help you put your mind at ease and figure out what types of workouts may be safe and healthy for you if you have a chest health condition.

If your pecs are merely weak, workouts like push-ups, chest flyes and dumbbell pullovers can all be impactful in helping your chest muscles grow and get stronger.

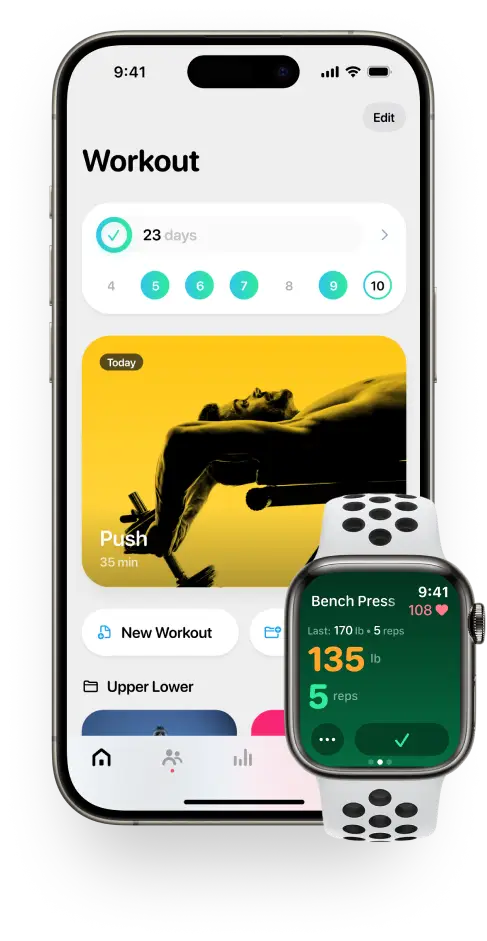

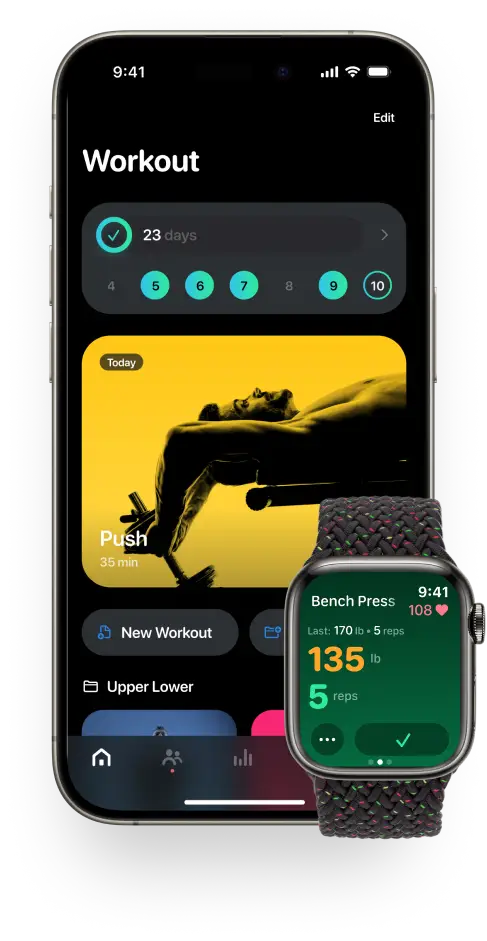

Bad chest genetics don’t have to mean bad workouts. The Flex App progresses as you do with plate tracking capabilities and auto progression. Get targeted workouts for strength, growth, and longevity.

References

David V. L. (2022). Current Concepts in the Etiology and Pathogenesis of Pectus Excavatum in Humans-A Systematic Review. Journal of clinical medicine, 11(5), 1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11051241

Swerdloff RS, Ng JCM. Gynecomastia: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. [Updated 2023 Jan 6]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279105/

Winkens, R., Guldemond, F., Hoppener, P., Kragten, H., & van Leeuwen, Y. (2009). Pectus excavatum, not always as harmless as it seems. BMJ case reports, 2009, bcr10.2009.2329. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.10.2009.2329

Yang, N., MacArthur, D. G., Gulbin, J. P., Hahn, A. G., Beggs, A. H., Easteal, S., & North, K. (2003). ACTN3 genotype is associated with human elite athletic performance. American journal of human genetics, 73(3), 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1086/377590

Related articles

Get fit with Flex

Build muscle & lose weight fast for free.

Available on iPhone + Apple Watch