How to Get Big Calves With Bad Calf Genetics

A guide to getting bigger and stronger calves with bad calf genetics. Learn how to optimize your calf muscles for growth.

So you’ve done everything to counteract your bad calf genetics?

Exhausted all your options and your stubborn calf muscles still won’t budge?

This muscle group is a total pain for even some of the most experienced weightlifters to grow. So if you’re struggling with small calves, you’re not alone.

However, the reason your calf muscles seem reluctant to make an appearance may surprise you. You can train and train all you want, but not all calves are created equal.

Are your genes sabotaging you from having superstar calf muscles? Today, we’ll look at good vs. bad calf genetics. We’ll go through the anatomy of the calf muscles, and a few of the genetic components associated with muscle growth.

Finally, we’ll come to some reasons why your calves may be stubborn to grow. Then, we’ll walk through the best calf growth exercises to target stubborn calves.

Calf muscle anatomy and function

So what are the calves anyway?

These babies don’t live on a farm. They live in the lower half of your legs. The back portion, opposite to the side where your shin lives is called the calf.

The calf muscle group is actually composed of two main muscles: the soleus and the gastrocnemius.

The gastrocnemius is the more superficial part of your calf, meaning it sits closer to the surface of your skin, while the soleus is deeper.

Both these muscles work together to plantarflex your ankles. Plantarflexion is a type of ankle movement where you move the foot across the ankle joint away from your body. In other words, pointing your toes.

You can read more about the calf muscles in Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Calf.

What are good vs. bad calf genetics?

When we talk about bad calf genetics, there are a few common indicators that we mean, these are:

Small Muscle Bellies

The muscle belly is the “meat” of your muscles.

Each person’s muscle bellies are different and this size is genetically determined. Although you can work out to create damage to the fibers of your muscles that cause them to grow over time, you’re not able to change the baseline shape of your muscle bellies.

That will be determined by genes.

Type I Muscle Fibers

There’s some research on muscle fibers to suggest that hypertrophic effects of type I muscle fibers kick in more easily after more time under load.

People with higher percentages of type I muscle fibers may find it tougher to see rapid muscle growth than those with more type II muscle fibers. For reference, type I fibers are your slow-twitch muscle fibers. We see high amounts of these fibers in endurance athletes.

Think about the typical build of a marathon runner.

These people are often long and lean with slim muscles that carry them across long distances.

Type II fibers are more common to see on sprinters.

They have thick, powerful muscles, more often than not that fuel their explosive power and are able to help them cross the finish line quickly across rapid bursts of running.

Why do some people have more type 1 than type 2 fibers? You guessed it: genes!

Both types of muscle are useful for different skills. A good balance of the two would make you super speedy and ultra-resilient to long bouts of training. Most people, though, tend to lean one way or the other.

And if you’re heavy on the type I fibers, there’s a good chance your muscles may seem like they’re not growing.

Why won’t my calves grow?

As we outlined above, bad genes are a reason.

But this is only part of the issue. For most people, there are a few other key factors and reasons why your calves won’t grow.

Overuse

Yes, you heard right.

You may actually be using your calf muscles TOO much.

Think about it. Every time you take a step outside the house, your calf muscles are fuelling your movement just to get you to walk.

What this does is create a repetitive pattern of movement. It’s great in terms of things like regulating your body fat to get a lot of steps in.

But repeatedly putting one foot in front of the other doesn’t create the type of movement necessary to shock your muscles enough to grow. Training your calves in the gym forces you to switch things up from boring, samesy movements that hinder your calf growth progress.

Not Enough Training Volume

Because you hold your weight on your calves all day, they don’t get a lot of devoted training time. They’re simply working to carry you through the motions of everyday life.

Training your calves frequently and with high volume will help counteract even the worst calf genetics. If you put in at least a little effort, even those with bad calf genetics should see some degree of improvement with training over time.

Lack of Progressive Overload

Simply running or walking around to train the calves doesn’t follow the principles of progressive overload. Load or repetition progression creates muscular adaptations and will force your muscles to grow over time.

The most obvious way to achieve progressive overload is with higher weights. But anything that increases the intensity of a workout can work. This includes things like adding sets and reps, more devoted training days for a certain muscle group during a week or shorter breaks between sets.

Lack of Devoted Training

This is potentially the simplest tip but the most important.

The way to really grow your calves?

Make them a priority!

When we think about our gym goals, a lot of guys are obsessed with Greek God workouts for massive shoulders and a coveted V-line.

Women often prioritize understanding how to get wider hips, build a slim thick physique or a shelf butt.

Guess whose goal is to get strong calves?

Usually no one.

If building your calves up is your goal, make it the first thing you do when you step into the gym, not an afterthought. The first muscle you train is usually the one you’ll have the most energy for. Your muscles are also the freshest when you begin a workout vs. when you’re finishing. Start with the calves if you really want to see them come together.

Exercises for Bad Calf Genetics

So you’ve tried everything and your calves still look scrawny and pathetic? Here are a few exercises you’ll want to throw into your leg day routine to help kick your calves into high gear.

Standing Calf Raises

- Set-Up: Stand flat on the floor with your feet hip-width apart. Point your toes straight forward.

- Action: Rise all the way up onto the balls of your feet.

- Muscle Activation: Fully engage your calf muscles as you come to the top.

- Descent: Hold for a moment, then slowly come down to flat feet with control.

- Reps: Repeat this movement for 12-20 reps. Aim to complete at least 3-4 sets.

Pro-Tip: If you find your ankles roll or sway you as you rise up onto your tiptoes, you may have weak ankles, weak calves, bad calf genetics or all of the above.

Focus on slow sustained movement. Keep your ankles straight. If you’re really struggling to keep your balance, hold on to a wall or machine at the gym until you can stay upright.

Add a light weight, from 8-15 pounds. It may not feel like a lot, since oftentimes any resistance it a lot for your calves. It can seriously increase the burn you feel, and it’s especially good as a soleus exercise.

Many commercial gyms also have a calf raise machine. Your gym may offer a standing calf raise, seated calf raise, or both.

Take some time to scope out the options and see which machine works best if you’re opting for this type of training.

Calf Raises on Step

This calf raise variation increases the range of motion. Not only do you get muscular strength work here, but you get a stretch in your calf muscles too!

To do a calf raise with a step:

- Set-Up: Find a step. You can do this movement with the steps at your house, or use an elevated step platform at the gym.

- Body Position: Stand with only the balls of your feet on the step and your heels hanging off. Keep your feet hip-width apart and your toes pointed forward.

- Action: Drop your heels so the balls of your feet are elevated on the step. You should feel a stretch through the back of your leg.

- Elevation: Push up and out of your toes to raise the heels, shortening the calf muscles (like in the above variation) and rise up onto the balls of your feet.

- Reps: Drop your heels all the way down beneath the balls of your feet to complete one rep. Continue this move for 12-20 reps. Aim for 3 sets.

Raised Heel Squats

This squat variation gets your soleus muscles and the other parts of your legs working all at once. For most people, raising the heels on your squat using a weight plate also lets you get deeper into the squat by putting your ankles in a more ideal position for getting low.

Raised heels take some of the strain out of both the ankles and the hips when you squat.

To perform raised heel squats:

- Set-Up: Grab a weighted plate or a squat wedge. Set it up so that the balls of your feet sit on the ground but your heels are elevated.

- Body Position: Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart or slightly wider, depending on your preference.

- Action: Drop your body down into a squat position. Keep your core engaged and your torso upright while you lower your body. You may want to clasp your hands together or keep them on your hips for stability. Push your hips out and back as you squat.

- Reverse: From the bottom of the movement, push up through your heels to drive your body back up to your starting position. Make sure your heels stay planted on your weight plate and don’t start to lift during the movement.

- Reps: If you are using weight, repeat this move for 6-8 heavy reps, or use 10-12 lighter reps for hypertrophy. If you’re new to raised heel squats, try them unweighted until you nail the technique.

The Takeaway

So whether your genetics are optimal to get huge calves or a little on the small side, there’s always a way to get them to grow.

Shorter or smaller muscle bellies are considered “bad calf genetics.” Two many type I muscle fibers and not enough type II fibers could leave you unable to put as much muscle on.

Some people also consider this an example of bad calf genetics.

Don’t get discouraged if your calves aren’t growing as quickly as you want them too. The calf muscles are a trouble growth spot for many people. Keep consistent and you should see small increases in calf size over time.

Hey! Do you think your genes suck? For more articles about potential genetic barriers to exercise and what you can do about them, here are a few can’t-miss articles:

References

Binstead JT, Munjal A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Calf. [Updated 2023 May 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459362/

Grgic, J., Homolak, J., Mikulic, P., Botella, J., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2018). Inducing hypertrophic effects of type I skeletal muscle fibers: A hypothetical role of time under load in resistance training aimed at muscular hypertrophy. Medical hypotheses, 112, 40–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2018.01.012

Herbison, G. J., Jaweed, M. M., & Ditunno, J. F. (1982). Muscle fiber types. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 63(5), 227–230.

Plotkin, D., Coleman, M., Van Every, D., Maldonado, J., Oberlin, D., Israetel, M., Feather, J., Alto, A., Vigotsky, A. D., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2022). Progressive overload without progressing load? The effects of load or repetition progression on muscular adaptations. PeerJ, 10, e14142. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14142

Related articles

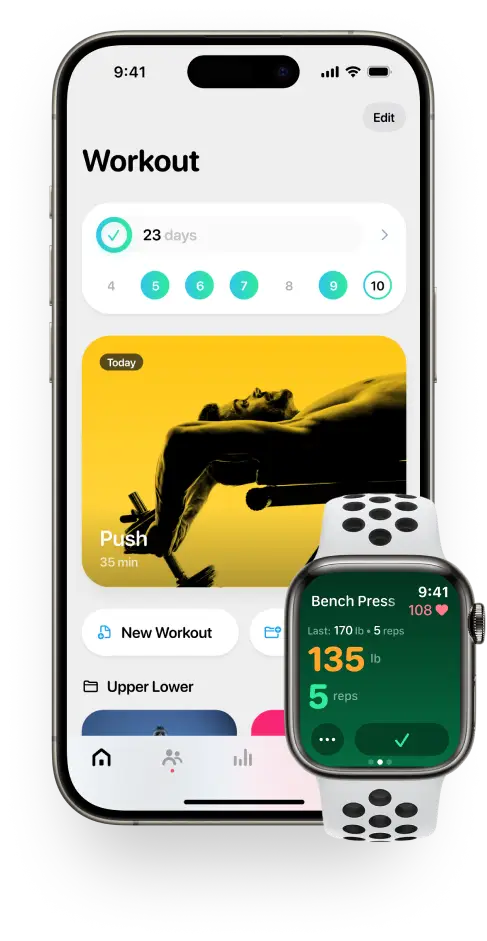

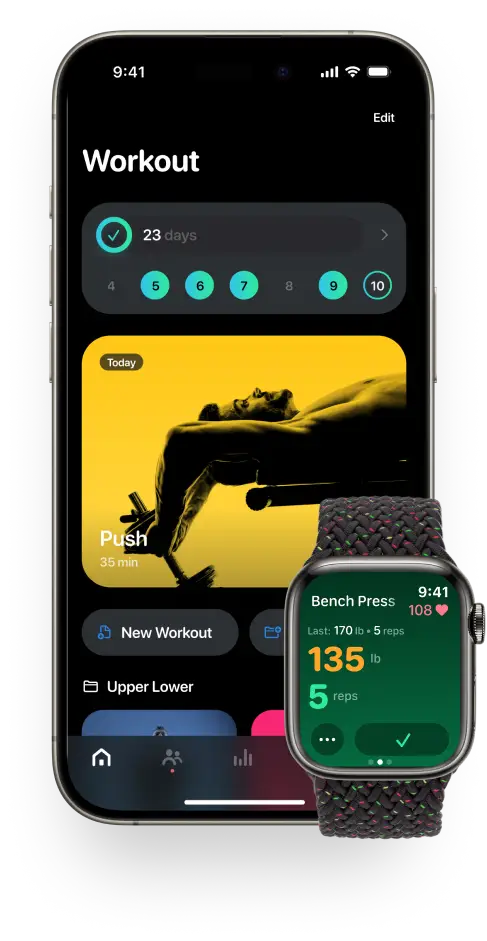

Get fit with Flex

Build muscle & lose weight fast for free.

Available on iPhone + Apple Watch